In my sessions with Richard Goode and Andre Watts, we dealt with a number of Schubert-specific sound and notation problems: different degrees of shortness and length implied by staccato dots, staccato dots with slurs, notes without specific articulations, and slurs. One very useful idea that Richard shared with me was that the portato (slurred staccato) effect could be accomplished well by the fingers alone. I’d generally used a combination of short finger attack and pedals; Richard’s suggestion was to play with very close fingers and to control the length of the note entirely that way. There are places where Schubert indicates portato in only one hand, as in the A-major Sonata, D 959, at measure 116 in the first movement. In this case, the pedal is not the best way to achieve this effect as it eliminates the contrast between the right and left hand’s articulation.

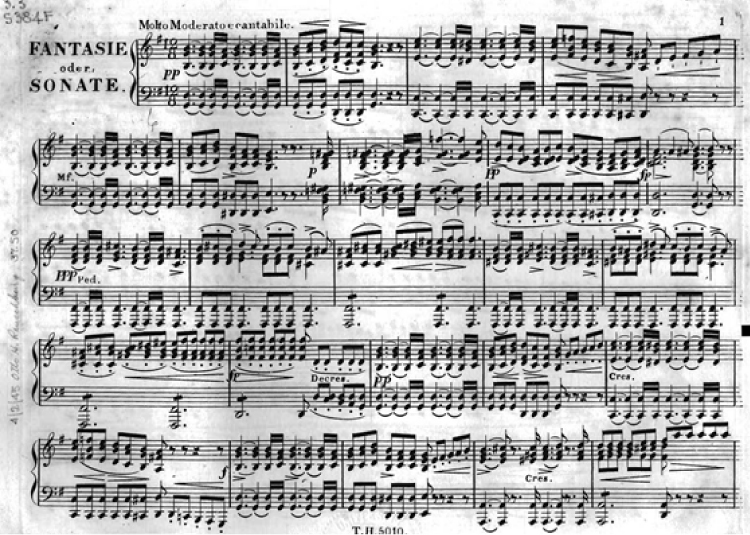

More complex is the articulation of the opening of the first movement of the G-major Sonata, D 894, where the phrases are each subtly different. Given that Schubert saw publication of this sonata, it seems reasonable to assume that at least some of these differences are intentional. That said, the possibility of achieving true legato octaves in measure 4 continues to elude my average-sized hands, but some differences in approach, shape, and tone should be possible.

Another important Schubert problem is dealing with notated accents. In Schubert’s manuscripts, it is often difficult or impossible to distinguish accents from diminuendo hairpins; different editions make different decisions. If you compare Bärenreiter and Henle, you’ll get the idea quickly enough. One odd result is the frequent crescendo hairpin leading to an accent in a context where the accent looks out of place. In the opening of the G-major Sonata, these issues come up right away, with phrases incorporating dots with slurs, slurs without dots, carats without slurs, and staccato dots without slurs.

The example above is from the first edition (the whole thing is on IMSLP). Not only do you have to make sense of the different ways that the eighth notes are articulated, but you have to wonder if it’s all intentional—it’s certainly intriguing that the second measure of the piece and the fourth system’s fourth measure are articulated differently (no dots the second time), although they are identical music in all other respects. Henle reproduces the text of the first edition in this case; Bärenreiter adds editorial (smaller) staccato dots to make it consistent. For me, it takes a certain effort to distinguish the smaller and larger dots.

In order to hold together the fantastically expansive first movement, having a strong sense of momentum is critical. There are enough overly slow performances out there (with cult followings on YouTube) already—this is music that requires motion; moderato is not adagio. Ernst von Dohnanyi’s approach in his last public recital is refreshingly spontaneous and unpedantic—many thanks to Andre Watts for steering me to this performance. The charm of the underlying dance rhythms in the second theme, the sense of forward motion that is always present, and the naturalness of the phrasing are virtues of this performance:

Of course, it is also easy to hear what are perhaps less than ideal—the opening rhythm is anxious, and the spaciousness of the opening suffers somewhat from what might simply be performance nerves.

Radu Lupu seems to hit a nice happy medium—and with a sound that glows:

Tempo unity is a big issue in any Schubert movement, of course, but this movement, with its spare writing and long-breathed phrases is especially difficult in this respect. And, when you think about how to do this while also controlling sound, balance, and articulation, and you’re playing in front of a famous pianist whom you admire . . . well, it’s easy enough to find yourself dealing with a certain amount of nervous tension, which prevents you from doing any of these things.

One especially memorable moment from my sessions with Richard involved the second movement of the G-major Sonata. After I’d played through the movement, Richard suggested that the opening could use a simpler, more song-like rhythmic treatment—I’d tended to feel it with a fair bit of dancing lilt—and proceeded to sit down and play it absolutely exquisitely with a far more straightforward sense of the pulse than I had managed. I was reminded of how important it is to support the sound in order to play the rhythm: often rhythmic flexibility is needed to overcome sonic inconsistency; when the sound is better, the rhythm fixes itself.